Pjorsa Source to Sea

This packrafting source-to-sea descent of the Pjorsa was undertaken in June 2017. All notes are based upon the conditions experienced at the time. We understand we had average water levels for the season. It is our understanding that the river flow below the dams near Burfell is regulated to 300 cumecs all year round.

Along the length of the Pjorsa there are long stretches of flat water or easy rapids. However, with the exception of the lakes and the final part of the river after Uridafoss there is always a fast current to help speed the paddler along.

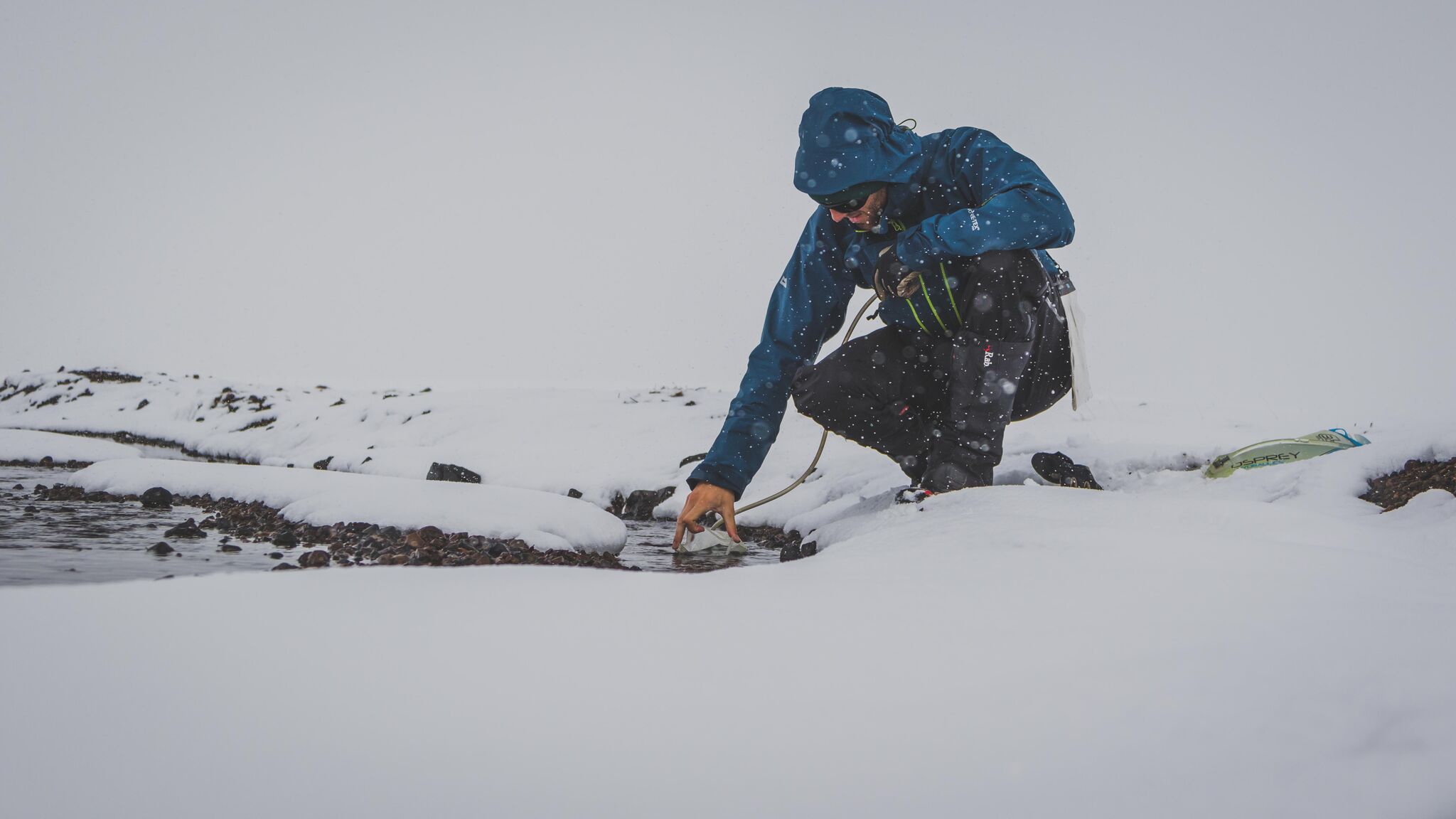

The source of the Pjorsa is a stream feeding a small lake at 64.984431° N, -18.023638° W. In June 2017 this stream was a snowfield but, in any case, is unlikely to be navigable at any time. For 15km from the lake outlet to the confluence with the river at 64.918000°N, -18.161281°W, the river is mostly unnavigable. Our team attempted to paddle part of it but regularly had to drag or carry boats around shallow areas – we would recommend ‘portaging’ this whole section unless water levels are much higher. A few kilometres from the lake outlet a spectacular mini-canyon cuts into the barren landscape with jagged rock formations and snow bridges waiting to great the adventurous paddler. The canyon contains four drops of various sizes (from around one metre to several metres). Unfortunately for three of these drops the entire river sumps underneath snow bridges, forcing (easy) portages. Due to the snow cover in June 2017 it was difficult to assess the feasibility and difficulty of the drops as only the exit pools could be easily inspect (sometimes only by paddling back upstream underneath the snow bridges!). This gorge could potentially make an interesting short paddle and deserves further investigation in warmer/wetter conditions.

For the 35km from the confluence to the lake the river is often flat with intermittent rapids up to grade 2/2+. One exception to this is a grade 4 rapid (64.893749°N, -18.217254°W) with a rocky landing approximately 4 km after the confluence. This rapid is much harder than anything else in this section and so its approach should be obvious. It is important to stop well above the entrance rapid as steep banks would make inspection or portage difficult lower down.

The southern end of the lake is dammed and there is no appreciable flow below it. This part of the river is also fenced off and so presumably access is prohibited, although it would be easy enough to follow on foot. An alternative is to paddle a man-made channel on the eastern side of the lake to a second smaller lake. From the southern end of this lake it is possible to trek 3 or 4km west, crossing the road near an emergency shelter, back to the main river. Accessing the river at the closest point (i.e. shortest trekking distance) is coincidentally just about where it becomes navigable again. To access the river here still requires that a fence is crossed, alternatively the fence line can be followed for at least several kilometres until it permits ‘natural’ access to the river.

For the next 25km the river is flat and split across many channels. In many places the river is scrapey but with good planning (and a little luck!) dragging or portaging the boats can be avoided – a good rule of thumb seems to be to always take what appears to be the most voluminous channel! As you continue downstream the river gradually increases in volume as the many channels begin to merge together. As this happens the crystal-clear water of the upper river gradually turns a silty grey, a symptom of the glacial run-off.

At 64.458889°N, -18.962275°W the river splits around an island. The river right channel goes at G3. Shortly afterwards at 64.416781°N, -19.053645°W a grade 4 rapid appears. In low water you can climb out on the rocky ‘bank’ (it’s actually part of the river and is likely to have a small amount of water running over it) to inspect. In these conditions the water all funnels river right dictating the line – in higher water more lines would open up but inspection would be harder.

At 64.391668°N, -19.099013°W is the first waterfall (4km from grade 4 rapid), can be run via various lines. Then another 4km to where river splits (64.359554°N, -19.154802°W) around an island with hard rapids (Grade 4-) on both sides. The 2 channels converge temporarily before almost immediately splitting again, stay river left and get out partway down this next channel – you’ll probably want to portage the next waterfall. After this waterfall there are some decent looking rapids in a deep canyon – access is difficult so it is probably easiest to portage approximately 5km past the next waterfall. After waterfall 3 rivers calms down to flat.

The next 7km to the lake are flat but very scenic. Be careful of sandbars near the start of the lake. Near the dam on its west bank you’ll see a small innocuous whirlpool on the surface – stay well clear (when you get back on the other side of the dam you’ll see what I mean!). On the other side of the dam pick a spot to put back on depending on your ability. The river gets progressively easier from the dam so don’t be put off by the dam’s discharge and the steep banks. After a couple of bends the river is flat again and stays like this all the way to the weir at 64.165460°N, -19.598425°W.

The weir itself has a strong towback and no weaknesses. It is probably best to portage on river left. 5km after the weir a waterfall is obvious on the horizon. There are various lines (some slides) split by small rock islands/towers, but generally speaking the left-hand side looks easier than the right. Land some way above the waterfall on the river left and scramble up ‘sand dunes’ to inspect.

Within 3km (G2-) you’ll arrive at the next waterfall. Again this waterfall can be run but is probably easier from the right hand-side (note the photo on Google Earth by robiswiss@falnet.ch is of Þjófafoss, not this one). Land river right to inspect as it would be difficult to ferry across from the left bank. The first few hundred metres after the waterfall consists of G4+ rapids in a mini gorge. After the obvious crux the rapids quickly get easier and there is nothing else of significance in this mini-gorge. This is not the grade 5/6 gorge mentioned here (which didn’t seem to exist, or as the river splits a bit around here, was a minor side channel we didn’t even see).

Soon after exiting the gorge you will arrive at a third waterfall, Þjófafoss, which will be a portage for almost all groups (supposedly severe criminals used to be thrown over this waterfall for their punishment!). Egress is reasonably simple but finding a way to get back to the river can be difficult due to steep cliffs. We landed on river left but from our perspective river right seemed like the better option.

From the bottom of Þjófafoss the river is at most G2- for 21km until 64.041172°N, -20.154574°W. Here the river splits around an island. We took the right-hand channel, scrambling high on the bank to inspect, which was a 750m G4- rapid. The rapid consists mainly of large wave trains hiding the odd hole. In particular be wary of a large hole covering a large chunk of the right-hand side of the river just before the two channels converge again – you will likely have been pushed right on the previous bend but try and get as far left as possible before the obvious final drop/wave/hole. Overall this rapid is much bigger than it looks when inspecting from the bank!

5km of easy water bring you to the next water, Budafoss (64.03110°N, -20.286935°W). We found this the hardest waterfall to spot from a distance so pay attention – essentially this is the first thing of any significance after the rapid detailed above. If you’re not sure get out and look! Land river left to inspect – the easiest line is probably hard left but portage is also easy.

From here the river remains easy until the obvious narrowing of the river a couple of kilometres above the ring road. This rapid is described here but is essentially a grade 4 wave train rapid through a gorge. The hardest part is right at the start (and can be avoided by paddling right around the rocks) and the river has eased by the time you cross under the old bridge.

From here it is best to stay right as this will allow you to paddle close to the top of the next waterfall with no significant difficulties (both the lead-in rapids and the actual waterfall are far harder on the left-hand side and would not be worth the risk in my opinion). This waterfall is Uridafoss and can run at grade 4 on right river via a series of slides and small drops. Portage is also easiest from the river right bank. There are likely to be tourists at this waterfall so be prepared for some observers!

Being Iceland’s most voluminous waterfall, paddling out underneath Uridafoss is an awe-inspiring experience. From here it is around 20km or so down to the sea along mostly flat and slow-moving water. Winds also tend to blow in off the sea and slow your progress. The scenery for this part of the river is not Iceland’s most exciting, but the likelihood of seals following you down the river more than makes up for it.

Eventually, by a deserted and desolate blank sand beach, you have made the coast! The waves here and strong and powerful – two experienced Icelandic sea-kayakers drowned at the Pjorsa river mouth in 2017 so it is advised to land in the protected ‘bay’ just before the actual mouth and walk the last couple of hundred metres.